Monte San Vito

hugged by the hills, kissed by the sea

The town

Monte San Vito

At the centre of the Marche region, between the hills and the sea; all the transport and connecting facilities near you.

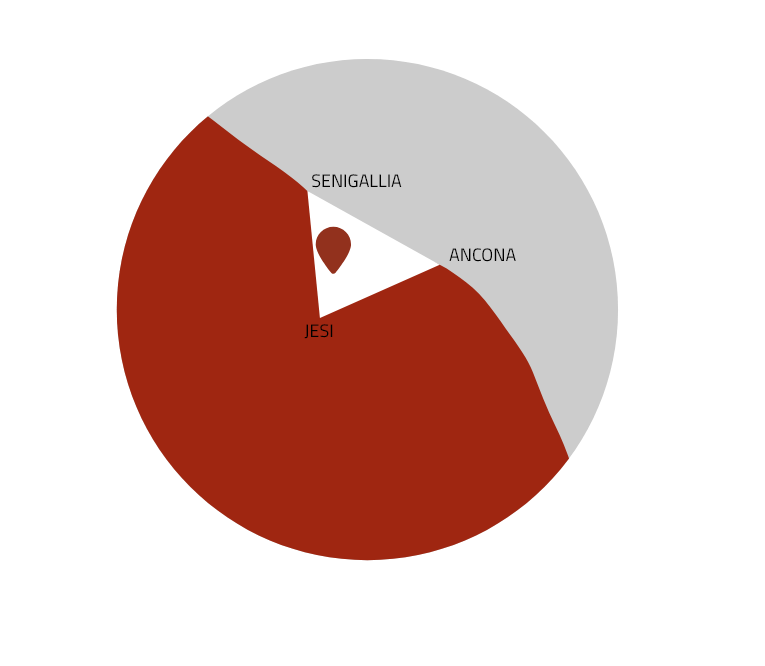

Monte San Vito is a borgo in the Marche region situated on a hill, at the centre of an imaginary triangle between the nearby cities of Ancona, Jesi and Senigallia.

The big dome of the Chiesa Collegiata di San Pietro Apostolo can be seen from almost all of the Vallesina area and it is a distinctive feature of the landscape.

Monte San Vito’s history

From antiquity to today

Already in the Lower Paleolithic, the territory of Monte San Vito was frequented by groups of hunters, who left traces of their passage in three locations (San Vito – Contrada Perello – Colonia Tiberi) where flint artifacts were recovered. From the San Vito lithic industry were found: some facial tools or hand axes and utensils such as scrapers, points, denticulate tools which suggest the presence of more or less evolved groups of Homo erectus; few ceramic and flint artifacts attributable to the Neolithic, also found in San Vito. Of particular interest is the discovery of a burial site in the San Rocco district—currently on display at the “Pigorini” National Prehistoric Ethnographic Museum in Rome—accompanied by grave goods consisting of 3 blades, 26 arrowheads, and a flint dagger. This tomb likely dates back to the end of the Copper Age or the Early Bronze Age. According to information that Angelo Massa derived from lost manuscripts, the origins of this important and contested fortified settlement are traced back to two ancient castles: Castel San Pietro (or Monte San Pietro) and Bitodunum, which later became Vitodunum, likely founded by the Senones Gauls in the 4th century BC.

The first written document mentioning Monte San Vito dates back to 1053 (“Carte diplomatiche jesine“), followed by a citation in the “Regesti Senigalliesi” of 1155. These documents suggest a probable consolidation into a single settlement occurring long before the 10th century. However, the town assumed significant historical prominence with the publication of the 1177 diploma issued by Frederick I Barbarossa.

This highly specific privilege removed the town from the jurisdiction of the Marquis of Ancona, placing it under the direct dominion of the Emperor. Furthermore, Monte San Vito was granted a vast territory including the castles of Morro, Alberello, Orgiolo, and Morruco, as well as six hamlets, including San Marcello and Antico. Added to this was territory extending to the sea, including the famous Castagnola Forest, with the exception of the Cistercian Abbey.

Following the Emperor’s death, the community of Monte San Vito returned to the jurisdiction of the Diocese of Senigallia, which later ceded jurisdiction to the city of Jesi via agreement. However, Jesi’s dominion over the castle was the subject of bitter disputes with the city of Ancona for many years.

At the beginning of the 15th century, the castle was occupied by the Malatesta family (following a failed attempt by Galeotto Malatesta about 50 years earlier). They consolidated the fortifications, building a fortress (rocca) that is now incorporated into the Town Hall.

Recognizing its strategic importance, Ancona appealed directly to Pope Martin V, but it was only under his successor Eugene IV (February 7, 1432) that they were able to obtain new sovereignty over Monte San Vito.

Unfortunately, the diatribes between Ancona and Jesi lasted for decades longer, finally ending when Leo X de’ Medici definitively assigned the Castle to Ancona, forcing Jesi to pay a heavy fine.

After a difficult period marked by calamities, brigandage, and famine, the town began a period of steady growth favored by its relative autonomy. This status was witnessed and directly recognized by Pope Paul V Borghese, who granted it the title of “Terra” immediately upon his election to the papal throne in 1605.

In the 1700s, the most significant event was the urban transformation brought about by the construction of the new Collegiate Church of San Pietro. The defensive walls were definitively opened, and their closed elliptical shape was broken to make room for a large temple with a dome approximately 10 meters in diameter and a new bell tower replacing the 16th-century one. This transformation, necessitated by the new ecclesiastical building, testifies to an urban evolution that was not always consistent but certainly continuous. It demonstrated the community’s will to no longer be enclosed within walls and a tendency to open up to new dimensions and spaces, even at the cost of sacrificing areas used for housing for centuries to allow for public use.

In 1710, the moat beneath the walls—an unhealthy place where livestock was often gathered—was filled in. Consequently, the road skirting the walls to the south-southeast became the Via Grande.

In the space in front of the old gate, the “muraglione” (great retaining wall) was built to reduce the excessive slope of the square and make the transit of carts less dangerous. This new structure met both aesthetic and functional standards, allowing the space to be used for the traditional “game of pallone.”

Along the new artery crossing the town, the La Fortuna condominium theater was founded in 1757.

Nineteenth-century transformations are clearly visible in cadastral maps, where crops, gardens, and vegetable patches—some still existing today—can be distinguished within the city walls.

The various confiscations of ecclesiastical property carried out around 1807, during the Kingdom of Italy, resulted in numerous transfers of ownership to both the public domain and new families.

In 1822, Eugene de Beauharnais (stepson of Napoleon Bonaparte, Duke of Leuchtenberg, and son-in-law of the King of Bavaria) sold 30 plots of land and a palace located in Monte San Vito to his sister Hortense de Beauharnais. These were part of the assets he received as an “appanage” when he was Viceroy of Italy. The assets had been requisitioned from the Collegiate Church, the Conventuals of Monte San Vito, and the Cistercian Abbey of Chiaravalle.

In the following years, Hortense de Beauharnais frequently stayed in Monte San Vito at her palace, located at what is now 17 Via Gramsci, together with her two sons. One of them, Louis Napoleon, would become the future Emperor Napoleon III. Damiano Armandi, the boys’ tutor and administrator of Hortense’s estate, would go on to be one of the protagonists of the revolutionary movements against the Papal States in Ancona.

Demographically, the population of Monte San Vito reached 4,000 units for the first time in the mid-19th century. This increase was also due to the strong intensification of cultivation, particularly marked in the second half of the 19th century: wooded areas disappeared, pastures were halved, and the cultivation of vines and fruit trees—which still characterize the landscape today—increased significantly.

Among the most important measures of the unified state were undoubtedly those regarding education, given that the illiteracy rate in the papal Marches was 70-90%. At the end of the 19th century, there were two schools in the Monte San Vito territory: the first-class rural school in the historic center, and the third-class lower rural school for boys in Borghetto.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Monte San Vito was a reality based on an agricultural economy and the sharecropping relationship. Agriculture was the vastly prevailing activity, around which most artisanal activities revolved; commerce was also expressed mainly in weekly markets and fairs. The sharecropping system guaranteed a certain social stability but hindered technical innovation due to both the force of custom and the sharecropper’s lack of interest in novelty.

In 1893, a handful of young people founded the “Sole dell’avvenire” (Sun of the Future) association, the first organized embryo of a socialist presence. In July 1901, the Provincial League of Chiaravalle included the “freedom to contract marriage without any employer imposition” among its demands. In 1902, a Christian Democratic Circle was formed in Monte San Vito (one of only 11 in the entire region), and in 1911 a new socialist circle was established in Borghetto.

The elections of 1920 sanctioned a complete overturning of the City Council’s composition, with a clear victory for the Socialist Party. The City Council unanimously decided to establish a municipal warehouse to provide for the purchase and resale of rationed and consumer goods at controlled prices, to combat the effects of the high cost of living resulting from the recently concluded war.

During the twenty years of Fascism, renovation and improvement works were completed on school buildings in both the main town and rural areas. A plan of works began for public lighting, the water-sewage network, and the cemetery.

The town’s position, in the immediate vicinity of the coast and Chiaravalle, made it a land of evacuees in 1943-44, significantly increasing the population present. A report by the German military command in February 1944 lists Monte San Vito among the territories where partisan guerrilla warfare was developing.

July 20, 1944, marked the Liberation and, at least for Monte San Vito, the end of the Second World War.

Wine

Monte San Vito is located in the same area where Lacrima di Morro d’Alba DOC is made. Castelli di Jesi Verdicchio Riserva DOCG and Rosso Conero DOC are also made nearby. Several wineries of these noble wines offer tastings, guided tours and events in the cellars and vineyards.

Olive oil

The territory of Monte San Vito is rich in olive groves and oil mills that produce extra-virgin olive oil of Marche. During the harvesting season, local farms offer certified products and guided tours to the facilities.

Sea

The closest beaches are in Senigallia, Marzocca and Riviera del Conero. They can all be reached in less than 40 minutes. Discover the seaside towns of Marche awarded with blue flags and provided with comfortable establishments.

Art and culture

Monte San Vito preserves churches, palaces and historical sites.

Just a few minutes away by car there are cities of high historical value, like Ancona, Jesi, Osimo and Senigallia. In less than an hour you can reach Urbino, Raffaello’s hometown: its historical centre is a World Heritage Site. You can also reach Fabriano, UNESCO Creative City, and the wonderful Frasassi Caves.